"A Christmas Carol" had already been in print for nine years when Dickens first began to read it in public: the first edition of 6,000 copies, printed in 1843 and paid for by Dickens himself, had sold out almost immediately, and within a year there had been eleven further editions. But the "readings" that Dickens embarked upon as a result of the novella's success were very much dramatic, as opposed to literary, performances: rather than simply read the story aloud, Dickens created a theatrical script from the text and added stage directions where necessary, even creating the voices and facial expressions for each character.

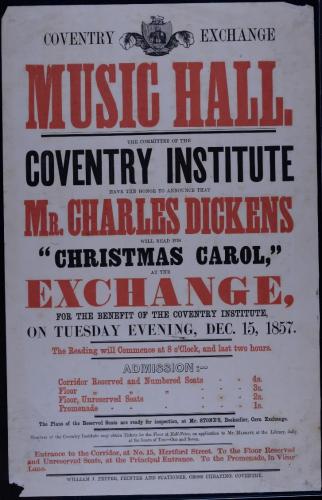

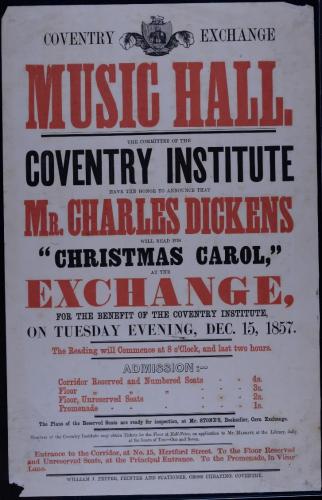

From the outset Dickens' public performances of "A Christmas Carol" were immensely popular: his first appearance at Birmingham Town Hall in December 1853 met with great acclaim and on 15 December 1857, he appeared at the Corn Exchange in Hertford Street at the request of Joseph Paxton, who had designed the new city cemetery at London Road.

Dickens' work had always been informed by the social issues of the day, and he was known for his commitment to good causes, particularly when it came to the welfare and education of the poorer classes. "A Christmas Carol" had in part been inspired by a speech that Dickens had given at the Manchester Athenaeum, an educational and recreational institute founded for labouring men and women; Dickens had also toured the tin mines of Cornwall and seen at first-hand the appalling working conditions of the people employed there, particularly the children. He wrote later that these workers had "for many years... been out of sight in the dark earth," and that as a consequence all "considerations of humanity, policy, social virtue and common decency have been left rotting at the pits mouth."

Dickens appeared at the Corn Exchange to raise funds for the Coventry Institute. This new enterprise had emerged from the Mechanics' Institution and the Religious and Useful Knowledge Society, which, despite some differences, shared a broadly similar aim: to promote literary and scientific pursuits among the working poor by means of books, lectures and concerts.

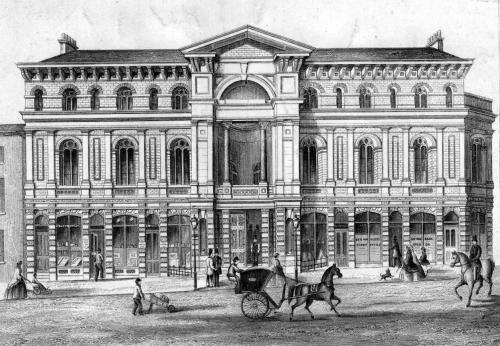

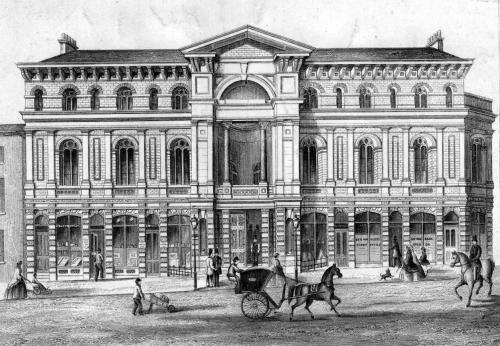

Its offices weren't that far from the Corn Exchange itself, an impressive building designed by James Murray, and built by Thomas Pratt. A settlement deed drawn up in 1854 states that the purpose of the building was "to maintain a public exchange for corn and other crops, and a hall for meetings and balls" and although it was used primarily as a corn market, the Exchange was indeed of a sufficient size to accommodate concerts, entertainments and lectures.

Dickens' appearance that December night was applauded in the local press for its "admirable dramatic power" and it raised £50 for the Institute. He was invited back to the city the following year for a dinner held in his honour, where he was presented with a gold watch manufactured by local firm, Rotherham and Sons. It was inscribed with the words: "Presented to Charles Dickens, esquire, by his friends at Coventry, in testimony of his kindness to them, and of his eminent services in the interest of humanity." Dickens would continue to perform "A Christmas Carol" right up until his death in 1870.

In later years The Corn Exchange was purchased by William Bennett, who also owned the Coventry Opera House. As the Empire Theatre it became one Coventry's earliest cinemas, and although it was destroyed by fire in 1931, a new theatre was opened in the same location in September 1933. Present at the Empire's grand re-opening was Colonel Wyley, owner of the Charterhouse, whose uncle had laid the foundation stone of the original Corn Exchange nearly eighty years before. The proceeds raised on the night went towards the Coventry Crippled Children's Guild: Dickens and even Scrooge himself would surely have approved... "God bless us, every one!"